How AI could help doctors predict cardiac problems in critically ill children

A unique collaboration between University of Toronto engineers and hospital physicians is pioneering the use of artificial intelligence – similar to an AI that helps detect earthquakes – to diagnose heart rhythm abnormalities at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children.

The innovative approach, which combines specially trained AI with the expertise of SickKids clinicians, could lead to significantly better health outcomes for critically ill children by providing faster and more accurate diagnosis of heart problems, the researchers say, as well as easing demands on clinicians’ time.

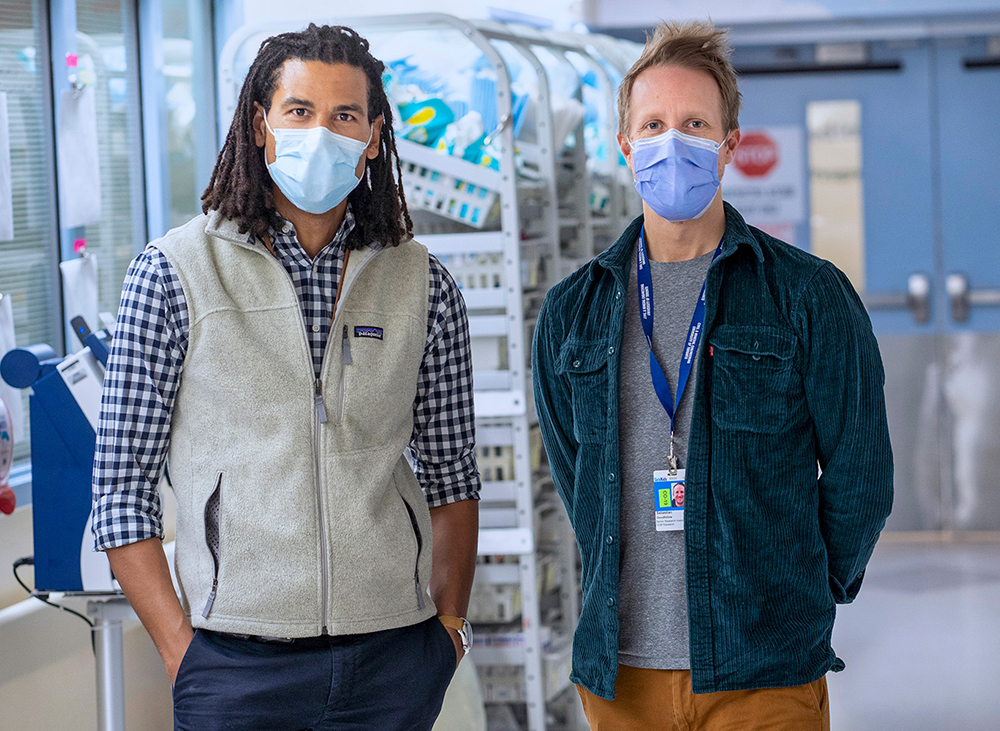

“This could help some of our most vulnerable patients, while also reducing stress on the health-care system,” says Mjaye Mazwi, a staff physician at SickKids and an associate professor at U of T’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

When the heart is functioning as it should, it beats to a regular rhythm – the familiar vertical spike followed by ripples that appear on a heart monitor. A heartbeat that is too fast, too slow or chaotic can cause severe complications and death.

Almost one in three children admitted to an intensive care unit experience a heart rhythm anomaly; at SickKids this affects as many as 700 children a year. These patients require constant monitoring, which places a high demand on hospital staff who are typically caring for other patients at the same time.

“The challenge is that clinicians cannot continuously monitor every bedside,” says Sebastian Goodfellow, an assistant professor in U of T’s department of civil and mineral engineering and a principal investigator at the Lassonde Institute of Mining. This can lead to a delay in detecting or diagnosing an abnormal heart rhythm, resulting in a worse outcome for the patient.

He and Mazwi, who is SickKids’ director of translational engineering in critical-care medicine, are developing what they believe will be a game-changing solution.

Prior to joining the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering, Goodfellow worked at a mining startup where he helped build AI models to scan geological data for certain patterns. In 2017, he was invited to enter a “computing in cardiology” challenge with a team from Laussen Labs, a research group at SickKids. There, he met Mazwi, who was interested in using AI to detect heart arrhythmias and was looking for help with the complex challenge of deploying it in the hospital. Goodfellow’s experience made him a natural collaborator.

The AI they are developing is being trained to recognize the warning signs of impending arrhythmia based on clinicians’ expertise and more than 10,000 electrocardiogram readings – a far greater number than even the most experienced clinicians would encounter during their career. Before being deployed with patients, the AI needs to be able to match or exceed the performance of a clinician, and accurately sound the alarm when one of these arrhythmia warning signs appears.

“We want this AI to partner with the best of human intelligence in a kind of collaborative intelligence,” says Mazwi, who is also research co-lead at the Temerty Centre for Artificial Intelligence Research and Education in Medicine. “We don’t believe that AI will replace clinicians, but we do believe that clinicians who use AI will outperform and replace clinicians who do not.”

The researchers are initially focusing on a specific type of irregular cardiac activity called Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia, or JET, that is especially tricky to detect because it involves subtle changes in the patient’s electrocardiogram. In those who have recently had corrective heart surgery, JET poses a significant risk of injury or death.

Detecting and treating JET early reduces this risk, which is clearly crucial for the patient. It also helps shorten the patient’s hospital or ICU stay, benefiting the entire health-care system, says Mazwi. Eventually, the researchers hope to develop AI models for detecting every kind of heart rhythm anomaly.

Although AI is making rapid inroads into many areas of life, including medicine, Mazwi says the process in health care is necessarily slower and more careful. An AI model must be tested and retested to ensure it will improve both patient outcomes and overall performance in the health-care system before it is used on actual patients. “We’re held to a much higher standard,” he says. “You don’t deploy an AI until you are perfectly sure it will provide gains over the current process.”

The research team at U of T and SickKids is collaborating with clinicians and researchers at other pediatric hospitals in England, Israel and Australia to test the AI models being developed in Toronto. Their two goals: to ascertain if the models work as well on similar patient populations in other hospitals and to sow the seeds for expanding far beyond Canada.

“The timely detection and diagnosis of heart arrhythmias is a challenge; it’s an even greater challenge for hospitals that do not have the funding and expertise that SickKids does,” says Goodfellow. “The real impact will be when we take this technology to underserved communities.”

This project is supported by funding from the Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research as part of the Joint EMHSeed and XSeed Funding Program, and the William G. Williams Research Directorship for Cardiac Analytics. It has also received a U of T Data Sciences Institute Catalyst Grant and a project grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

By Phill Snel

This story originally posted by U of T Magazine in the Spring 2023 issue