CivMin PhD student Emily Farrar, an admitted foodie, is finding a way to introduce flavour to alternative meat using cultivated beef fat from a lab. The astounding process is recreating real animal fat without harm to animals.

Ahead of the United Nation’s Sustainable Gastronomy Day on June 18, 2024, CivMin chatted with Emily Farrar to learn more about this entrepreneurial endeavour, completely different than the research field they’re in, to grow beef fat in a laboratory environment. The resulting impact of this research could see real beef flavour in foods, without the slaughtering of animals, as well as an impact to climate change through reduced emissions.

Farrar is pursuing a PhD in the Department of Civil & Mineral Engineering at the University of Toronto under the supervision of Professor Marianne Hatzopoulou.

Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

My name is Emily Farrar, a PhD student at the University of Toronto. I’m originally from the southern U.S., where I studied civil engineering. For my master’s, I studied climate change mitigation and civil infrastructure at UC Berkeley and worked for a couple of years at a research institute where I advised corporates on the commercialization of early-stage climate tech.

I came to Canada for my PhD, as I realized I wanted to do more quantitative analysis for emissions modelling. Now I’m at the University of Toronto working with Professor [Marianne] Hatzopoulou. Then, partway through my PhD, I also took on Professor Shoshana Saxe as a co-supervisor. Right now, I analyze how transit or urban growth scenarios impact GHG and air pollutant emissions. Early on in my PhD, I researched air quality measurements for community science.

You have an entrepreneurial endeavour, besides what you’re already doing as a graduate student here, right?

Yes, I co-founded a biotech startup called Genuine Taste. It’s quite a different field from my PhD.

This effort was born during the pandemic. Funnily enough, I never thought I was going to do entrepreneurship. Ever. But I went to a few workshops at U of T on women in STEM and entrepreneurship. And I thought, okay, this sounds like an interesting career path I’d never considered. And then I met my co-founder and everything clicked – it was an opportunity to combine my passion with food and sustainability and his expertise in biotech. Over the past two years, we’ve worked to grow the company.

Why did I pick a food tech startup? I was really interested in it from a climate change mitigation perspective. I think that’s where it overlaps with my background in civil and environmental engineering. I am very passionate about commercializing a new technology that has the potential to reduce emissions.

Currently, the plant-based meat sector is really struggling with customer adoption, as the products don’t really taste good. We’re working on cultivated fat as an ingredient to improve the juiciness and mouthfeel of alternative meat.

What is cultivated fat?

Essentially, you are recreating real animal fat without harm to animals. You isolate stem cells from an animal, say through a biopsy, then cells are cultured in bioreactors with nutrients and media, and then you end up with a final product that very closely mimics conventional animal fat.

Instead of muscle, which most of know as meat, you’re targeting the fat because that’s where the flavour is. Is this happening now? Is it being made?

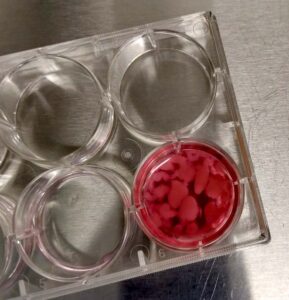

We’re currently culturing beef fat at benchtop scale. In startup terms, we’ve developed an ‘MVP’, or minimum-viable product. And we recently sold our first sample to a global food corporation, and they are testing our ingredient in an alternative burger.

What you’re looking to do is to make it sufficient and scale it. This is more ethical as you’re not slaughtering animals, right?

Exactly. You can take a sample once through a biopsy and then rarely have to re-isolate cells from an animal. You just keep using the same cells, growing new material from it. There are both ethical reasons for this and sustainability reasons.

One of the biggest sectors that contributes to greenhouse gas emissions is the food sector. Around 15 to 20% of global greenhouse gas [GHG] emissions come from animal agriculture – cows produce a lot of methane which is a driver of climate change. And much of the world’s agricultural land is used to produce crops for the animals we eat – it’s a pretty inefficient process. There have been a few studies about the potential environmental impact of cultivated meat. It’s anticipated that if you produce it with renewable energy, it’s estimated it will be more environmentally friendly than conventional meat.

Are you able to grow the muscle fibres as well if you want it to?

Yes, we could – it’s the same technology. This is all tissue engineering, but we picked fat for commercial reasons – fat is incredibly important for flavour and consumer adoption, and you need smaller volumes to deliver on that value. This is a strategic approach while the industry works to lower unit prices.

How did you decide you wanted to go ahead with this? You’re an engineer – the other founder’s a biophysicist – how do you come into the picture and what is your contribution here?

I wanted my work to have an immediate impact on the world, and I wanted to drive forward the commercialization of a novel technology. Also, it’s fun. Entrepreneurship is great for networking, meeting people, learning about amazing new ideas. Many of the skills I have gained directly feed back into my arole as a PhD student. For instance, you can get really good at public speaking and science communication.

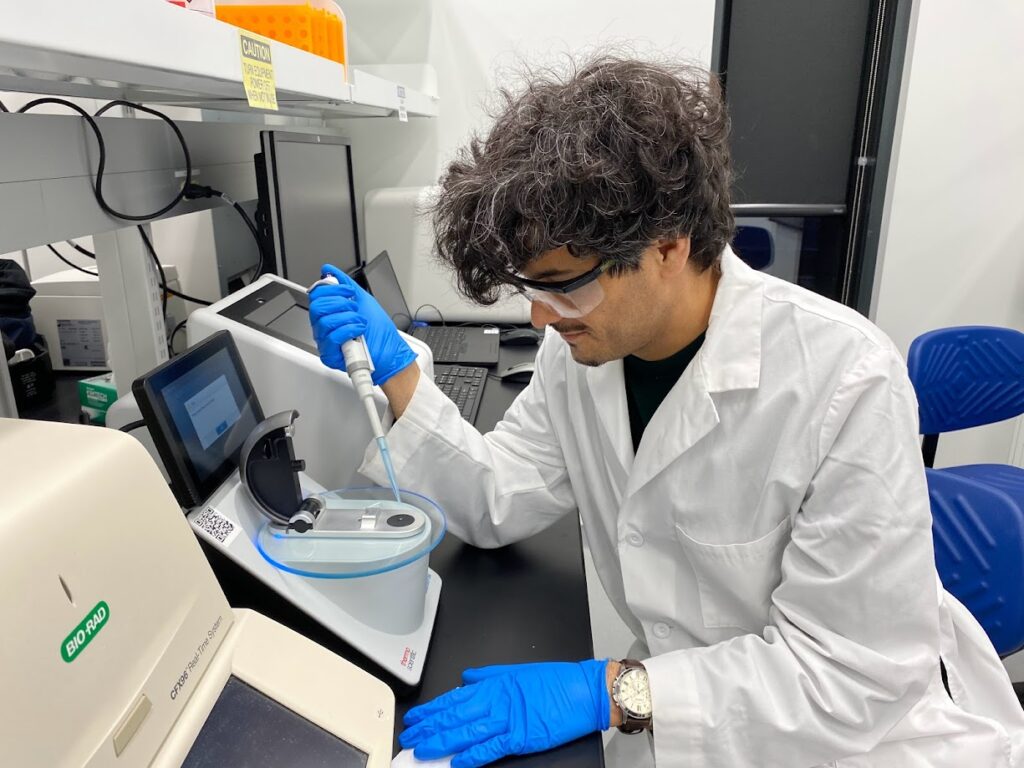

Within the company, my role is to work on commercial strategy and fundraising. I talk to customers and investors, refine our go-to-market strategy, and coordinate with project partners. I also do quite a lot of grant writing, which is pretty important for an early-stage hard tech company. I also assist with a portion of the technical work. I applied, and was awarded, a Mitacs accelerate project in which I’m working on an optimization project – sort of a machine learning optimization algorithms for reducing the number of experiments you need to grow cells more efficiently.

Who is your co-founder?

My co-founder is Pooya Mamaghani. He has a PhD in biophysics from the University of Cambridge and an MSc from UBC. During his PhD, he studied the interaction between stem cells and scaffolding (in essence, the matrix that the cells grow within). In the lab, he’s developed a scaffold that is very well suited for fat tissue.

He’s been a great asset as a co-founder, as he is not only incredibly technically talented, but he is also an experienced entrepreneur. As a first-time founder myself, it helps to have a team member who understands the space.

Did you meet virtually first or in person? And did you? Is there been any help or have you gone to the hatchery here at all for any help at all?

We started off campus. My co-founder was a member of Antler Canada, a VC [venture capital]-backed incubator. It’s based in Toronto, and he was in their first cohort. We pitched our idea to their team and were one of six out of over twenty companies to receive pre-seed funding. And that’s how we were born.

Help me understand seed funding – it is the beginning and what else?

Pre-seed funding is typically invested based on a good idea and a strong team. For hard tech companies, it’s very, very common to have pre-seed funding because you need resources to build your idea and refine your commercialization pathway. Usually, you raise a pre-seed round from angel investors, family, friends and early-stage investors.

Once a company has good commercial traction (think lots of interested customers) and has demonstrated that they have a unique, scalable technology, then they start raising larger rounds and/or bring in early revenue.

Where is this going? What’s your ultimate dream?

My ultimate dream is for us to create sustainable, ethical ingredients that don’t compromise on taste. I want to successfully scale up this technology and be part of the effort to make it accessible for any consumer that wants to try it.

You’ve made this alternative fat. Have you tasted it? Have you cooked with it?

I have, indeed, tasted it. I haven’t cooked with it, though, because it’s a very, very precious resource at the scale we are producing it. We recently sent a sample to an academic team at the University of Guelph that specializes in alternative fats for third-party feedback. And as mentioned, one of our customers is currently developing an alternative burger application in which they will test our fat.

A bit more about Emily:

What attracted you to U of T?

It was my supervisor, Professor Marianne Hatzopoulou. I was impressed by her work, and when I met her I knew she would make a wonderful mentor. I also came for a visit before I made my decision and fell in love with the campus.

Was U of T or Canada even on your radar?

I was interested in living in a new place, but the main reason I chose the university was for my supervisor.

Do you have any go-to place that you like to go for either for a snack or a meal or an alone space on campus or otherwise?

On campus, I love going to the Arbor room, a cafe at Hart House It’s a really great place to work if you like some ambient noise, and they have very tasty food. .

In Toronto, let me think… I really love the Toronto Reference Library – it looks like a spaceship. That’s a fun environment if you ever need to study off campus. And let’s see, I used to live in the Annex, and there’s a trail where you like hike up to Casa Loma, if you go up Spadina and hike up the stairs, and then you can connect to a ravine and walk all the way back down to downtown Toronto through the trail system. I love that. I’m a big hiker.

You moved to Toronto. How did you find Toronto? Because now you’re, you’re an international student. Any culture shock or was it very different here in Toronto? Toronto is known as a very multicultural city.

I grew up in a small town in the southern US, and Toronto is very, very different from that. But I also lived in the Bay Area in California and I find, at least in North America, cities are pretty similar to each other. There is a pretty similar living experience in terms of multiculturalism, food, cost of living, social life, etc. Because of this, I didn’t feel too much culture shock.

I’ve been able to enjoy Canada and I’ve experienced the city slowly returning to normal [after the pandemic]. One thing I really love about Toronto, or Canada, is it’s a little bit less capitalistic than America, and there are so many great shared resources (think free ice-skating rinks and pools throughout the city). I love that kind of thing. I feel it’s a little more community oriented.

And tell me something about all kinds of different nationalities or food.

I’m a big foodie (if it was obvious from working on a food tech startup). I love trying different cuisines and I feel like I’ve eaten foods from all over the world here.I think Toronto is unique. For example, in the Bay Area, or California, you might have really good tacos and really authentic south-east Asian food, but Toronto has everything. Everything.

Do you have any hacks, or words of advice, for somebody who’s a newly arriving graduate student at U of T.

I would say take advantage of all the resources that the university has to offer. When I first started my PhD, I joined the women in engineering group at U of T [GradSWE, Graduate Student Women Engineers]. It was a great way to meet people outside of the department, learn about different opportunities like entrepreneurship on campus. I think it’s also critical to be inperson as much as possible. I think starting in the pandemic made me really value face-to-face collaboration.

Is there something unusual you have a great talent we wouldn’t know about otherwise that we asked some special skill or some neat thing that happened in your life that you think is memorable?

I had an internship where, this was during my undergrad, we were water quality monitoring, and I had to swim in alligator-infested rivers. This can be my interesting story.

It was a power company, and they had to monitor the impacts of discharge on the waterways. The way they did this is they had transects upstream and downstream of the plants, where they installed poles underwater and zip-tied water quality monitors to those polls. We had to swim to place and retrieve them. It was completely cloudy, muddy water. You would swim around trying to find and touch the water quality devices. It wasn’t that deep, and it was near the banks, so about four feet deep. But it had to be deep enough that if the tide went down, it would still be submerged, so it was a bit of guess work where the devices were. So, needless to say, I became a strong swimmer after that!

By Phill Snel