Beyond the streets of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, lie the Islamic holy sites of Mina, Jamarat, Arafat and Muzdalifa. These sites are the destinations on an annual pilgrimage, called the Hajj, which all able Muslims are called to complete once in their life.

The sites and surrounding areas remain unused for much of the year, but during the Hajj, as many as two million people visit during the five-day pilgrimage period.

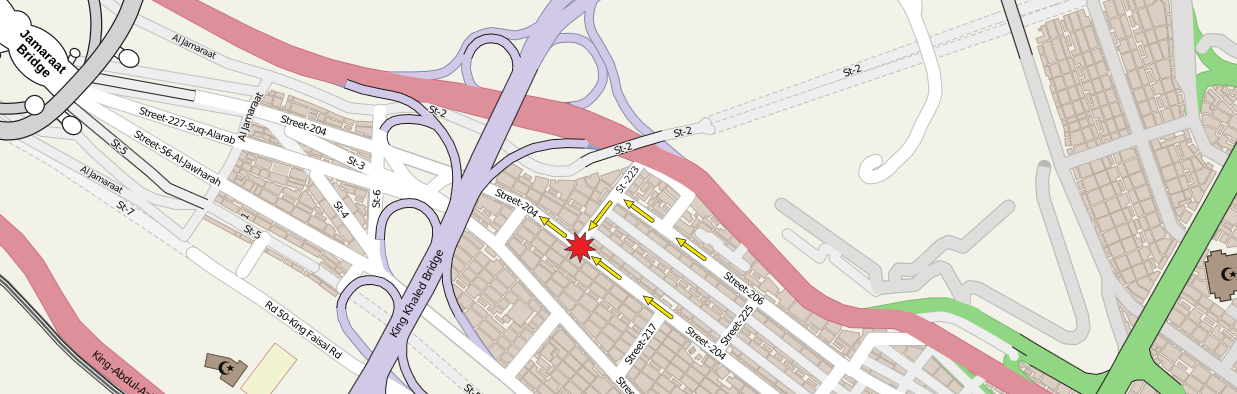

Tragedy struck on September 24, 2015, when a crowd collapse caused the death of between 700 and 2,000 pilgrims, according to varying reports. The crush happened at an intersection where two streets merged into one. The confluence of people from both streets increased crowd density to five or six people per square metre. People were suffocated and trampled as the crowd swelled in size.

“Densities of two people per square metre allow people freedom to change direction and speed, but at densities of four or more people per square metre, you lose that freedom,” said Prof. Amer Shalaby, a crowd management expert. “You become a water droplet in a flow of water; you can’t choose your path, stop or change direction—you must keep moving with the crowd.”

For the people who found themselves at that intersection, they could not escape and were forced onward by the crowd behind them. By that time. there was nothing that could be done to prevent this tragedy.

Although Saudi officials use various measures to manage the flow of people, including video cameras, on-site crowd control staff, timed schedules and alert systems, they were not sufficient to prevent this tragedy.

In order to avert a similar calamity at future Hajjes, officials are exploring technological innovations and smartphone apps for more individualized alert systems.

“Apps that alert visitors to potential problems in their own language could provide visual, actionable cues,” said Shalaby. “For example, when a particular area is busy, the app could use a colour scale to indicate crowd density at a given time, similar to the way mapping apps provide live traffic data.”

While effective and timely communication with visitors can help to prevent future tragedies, it is not a failsafe solution. Changes to transportation and infrastructure, developed over the past few decades in response to past crowding tragedies, need to continue to accommodate the influx of pilgrims.

The tent city surrounding the Hajj sites, for example, is now built with fire-resistant tenting material, a change implemented due to fire outbreaks in pilgrim tents.

The renovations to Jamarat and its three pillars are the most recent improvements to a Hajj site. They were built in response to annual crushes and stampedes at the site. Pilgrims now throw stones at three oblong walls (formerly pillars) to complete one of the Hajj rituals, a symbolic act for stoning the devil. Visitors access these walls from five different levels; access points to the walls vary depending on which direction the visitors are coming from, alleviating congestion and bottle-necking. Since the completion of the Jamarat Bridge as it is called in 2006, there have been no major incidents at the site.

Not all improvements are permanent fixtures; organizers have been improving mass transportation by using more than 15,000 buses to help manage the flow of visitors. These buses can also contribute to congestion in and around the Hajj sites, and the streets and routes connecting the sites—some as long as 20 kilometres—have not yet undergone improvements in engineering. This year’s crush happened on these roads.

The issue of congestion and crowd density will only continue; after 2015, officials will no longer enforce annual quotas on the number of pilgrims allowed at the sites during the Hajj. An estimated five million pilgrims will descend on Mecca for the 2016 Hajj and that number is expected to increase to 30 million annually over the next five years.

The crush on September 24 was not the only fatal incident in Mecca that garnered international attention this year. On September 11, as the city was preparing for the Hajj, a crane collapsed in the Haram Al-Masjid (the Grand Mosque), killing more than 100 people.

The Grand Mosque is the greater focus of Shalaby’s recent work in the region.

Unlike the Hajj sites, the Grand Mosque experiences steady use throughout the year, with peak periods during the Hajj and Ramadan. The Grand Mosque is now undergoing an extensive expansion to increase its capacity from 500,000 to 1.6 million visitors.

The quotas in place for the number of Hajj pilgrims are based on the expansion and its capacity for each year of its construction. The quotas will be lifted when construction is complete.

Shalaby’s work looks at crowd flows in and out of the mosque, as well as public transportation to and from the centre of Mecca.