Engineers and the environment: Finding the path

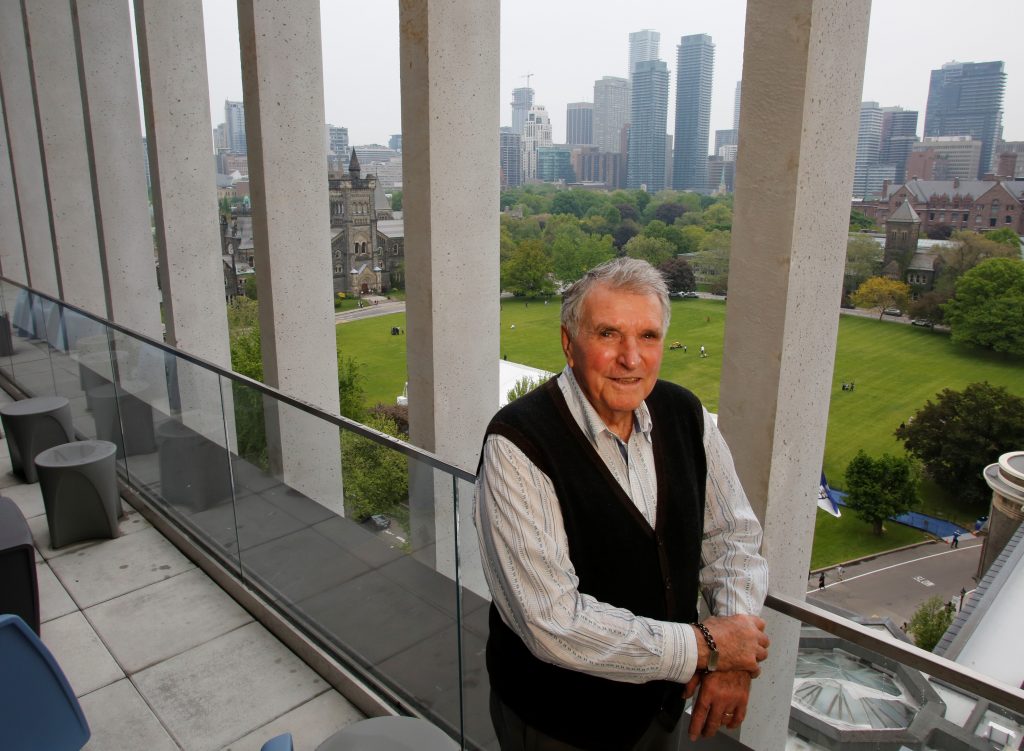

An Australian who only planned a stopover in Canada at the beginning of his 1954 travels, Barry Hitchcock (Civ 5T8) found himself in love and stayed. A degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Toronto, some time back home “down under” to work, then a return to Toronto, meant a lot of slow travel by sea in the era before travel by jet was common. The pace of long distance travel might have been slow at first, but Hitchcock soon found himself in the fast lane of civil engineering and coming to terms with environmental concerns.

–

“Highway Fight Tonight” trumpeted the newspaper headline. Hitchcock stopped in his tracks. Seeing the words in print while on his way to a routine Hamilton, Ont. city council meeting, he immediately knew the usually easy approval process had drastically changed for major construction projects.

It was about 1967. Hitchcock had arrived on behalf of the Ministry of Transportation Ontario (MTO) to present a plan for a Dundas, Ont. highway bypass across a valley for approval. This usual mere formality met unusual local resistance for the first time in his experience.

In this case, the MTO backed away. “I think that might have been one of the tipping points of the Environmental Assessment Act (enacted in 1975), which happened regarding highways,” recounted Hitchcock.

Hitchcock now believes only legislation will work to make builders more responsible towards their environmental impact. “Engineers are not going to do this on their own. It has to be enacted in some kind of regulation, or law, that they have to do it.” Hitchcock added, “So that the client understands then that they’ve got to pay for that. They’re not going to pay an engineer extra money unless they see a benefit.”

Previous to the Hamilton council meeting, big civil engineering projects had usually been met with enthusiasm in the communities involved. A new highway, railway, bridge or other big project meant prosperity to the area in the form of ease of shipping, local jobs, or modern conveniences more easily accessible. There never seemed to be a downside.

The Dundas bypass was the first time a major project failed to thrill the community. From then on, major civil engineering projects had to consider more than just optimal methods for construction, but had to more cautiously include local concerns and the local wildlife and environment.

Hitchcock’s past experience with major projects having environmental impact would prove significant in the course of his career.

“I wanted to be in some career, or profession, where I could work with the resources of the planet for the benefit of mankind.”

Engineering start

Hitchcock’s first association with engineering was with the Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission of New South Wales (Australia). “I wanted to be in some career, or profession, where I could work with the resources of the planet for the benefit of mankind. That seemed to be well in line with that kind of ambition,” said Hitchcock.

“I graduated from high school in 1947 and at that time the universities were crammed with returned service men and there wasn’t much opportunity for we school kids to get into university. So the New South Wales government had a program they called Cadet Engineers, so they would hire kids fresh out of high school and commit to pay for their education and put them through a training program working in one of the government ministries.

It was a six year program where I moved around different departments from the design of irrigation works, design of dams, doing hydrographic surveys, and land and construction surveys. I got experience in all of those fields over the six year period while I attended the Sydney Technical College (later University of New South Wales) at night, with some day courses they gave time off to complete. That got me a diploma in civil engineering.”

Unexpected environmental impact: The Snowy Mountains Scheme

When asked about how engineers used to think about the environment, Hitchcock replied bluntly, “I don’t think engineers thought very much about the environment then. I don’t know whether the word ‘environment’ was a word that was used in those days.”

“Looking back there was an environmental impact from the work that I was doing in irrigation. Irrigating parched lands in western New South Wales. What the agriculturists didn’t understand was below the surface there was a layer of salt, so when they irrigated it, the salt came to the surface and poisoned the ground. That was my first experience with an environmental impact; it was a bad impact that wasn’t foreseen.”

“I was in a way involved with the Snowy Mountains Scheme,” recalled Hitchcock, “which was the biggest engineering project worldwide at the time. I was doing hydrographic river flow measurements in the high country. The Snowy River flowed out of the mountains into the Tasman Sea – a short distance. So the wisdom was we were wasting all that water running into the ocean. We should be diverting it west to use the water for irrigation and open up vast tracts of land, and also generate electricity.”

“The Snowy Mountain Scheme was a system of dams and tunnels to divert the water that was flowing east into the western rivers so that there was an abundance of water flowing west and used for opening up new areas for irrigation.

“The worst thing that happened was that the Snowy River, being deprived of a lot of its water, deteriorated not only the river, but the land and the people who depended on the water. That was an environmental impact that was not recognized when they built the Scheme. Since then they’ve tried to remedy that by periodically flushing water down the Snowy.

“There’s two examples of environmental impact that were not foreseen by engineers,” he concluded.

Finding new homes around the world

Hitchcock’s family is no stranger to long distance travel coinciding with history. In fact, he can trace his family’s lineage in Australia to some of the original prisoners exiled to the penal colony then known as “New Holland”.

“Myself, I go back to the founding of the colony in Sydney (Australia). My great-great-grandfather was a convict who was transported there in the first fleet that founded the colony (in 1788). He had been convicted in the Old Bailey for stealing some cloth in South London. The sentence was transportation to Australia,” said Hitchcock.

“My great-great-grandmother came on the second fleet in 1790 and was the first ship of that fleet, called the Lady Juliana, with women convicts. She was a 15-year-old when she was convicted of stealing from her mistress some lace and cutlery,” recounted Hitchcock, before adding, “They got married in 1790, soon after her arrival in the colony, and they both got their ticket of leave and a grant of land that they successfully farmed Their descendants in my line achieved prominence in the business, science and theatre arts.”

In 1954 any travel from Australia required an enormous time commitment. Hitchcock settled on a plan to embark on a five-year trip, with his first stop slated to be in Canada.

Three weeks by sea to reach Vancouver, followed by a week-long train trip to Toronto, saw him arrive the very day Hurricane Hazel struck the city. The October 15, 1954 storm saw devastation wrought by nature’s wrath unlike any in local memory.

“There was a whole community washed out in the hurricane in Etobicoke (now part of Toronto). That was in the Humber River. The housing community in the Humber River flood plain. And they just got washed down the river into Lake Ontario and many people died. That was the day I arrived in Toronto,” reflected Hitchcock.

He had not planned on staying in Canada, with a view to still cross the Atlantic for his expected trip to England, but fate intervened. Betty, his love interest, became his bride.

U of T connection

“I applied for a license with Professional Engineers Ontario at that time, and they didn’t give it to me,” said Hitchcock. “I couldn’t see the point in getting a license by passing the exams they set, which probably wouldn’t count outside Ontario.”

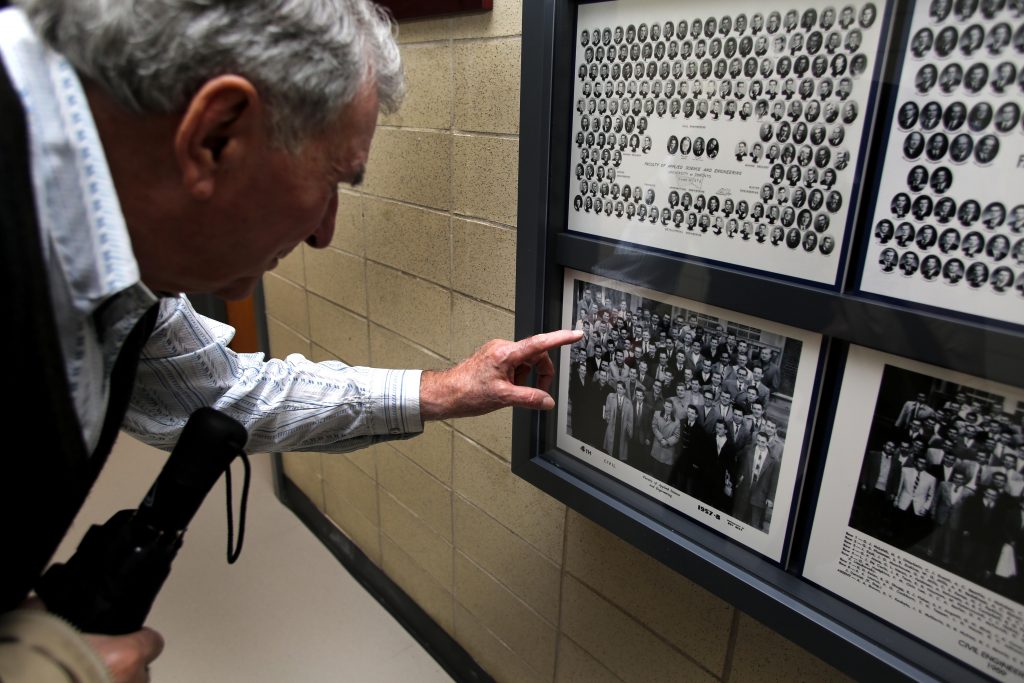

“So (in 1956) I came and talked with Professor (Carson) Morrison at the University of Toronto about getting admitted to the University here. They admitted me in the third year, and so I did the third and fourth years to graduate in 1958.”

To put his graduation year in perspective, it was two years before the present-day Galbraith Building was opened in 1960.

Asked if he attended Survey Camp, Hitchcock quipped, “No. I had worked as a surveyor and they thought I was so good at it that I could have probably taught the subject. So I didn’t go to the Survey Camp, but I did go to the reunions. My classmates would talk about Survey Camp. It was the main topic of conversation whenever we would have a reunion, so I thought I should go when they had a reunion there to see what they were talking about.”

Canadian career

After two years back in Australia, working as resident engineer constructing a supertanker berth in Sydney Harbour, Hitchcock returned to Canada in 1962. This time it was only a two-week journey by ship, representing technological improvements in travel.

While working for Giffels Associates Limited, Consulting Engineers & Architects for several years, then American-owned, the chance came to buy into the company to form a fully Canadian-owned arm, so Hitchcock joined the plan. It would turn into a 31-year career.

“We grew the company into one of eminence in Ontario in the field of transportation and municipal infrastructure.”

“We addressed the environmental issues in the 1970s and that might have been the beginning of when the MTO started doing environmental impact studies with all of their planning. And then it became the Environmental Assessment Act which was a requirement to do before any public works projects proceeded. Not just highways, but any public works.”

By 1991 Hitchcock became president of the Professional Engineers Ontario, and was afterwards appointed to the board of Engineers Canada in Ottawa.

In 1994, after chairing a national task force to develop guidelines for engineers with respect to the environment, Hitchcock produced a report. According to him, “when they developed these guidelines they sent them out to the provinces for ratification, but I surmise that since some of the guidelines would require government legislation for engineers to comply, it was never ratified. As far as I know, that report is sitting on a shelf in Ottawa never been used.”

“Engineers should be responsible for the environmental impact; not just for the design and construction and use of the product, but also its life cycle. It’s eventual decommissioning, and so on. The entire life.”

Responsibility of engineers

Hitchcock is unabashedly passionate about his gestalt views regarding the place of engineers in the world. “Engineers should be responsible for the environmental impact; not just for the design and construction and use of the product, but also its life cycle. It’s eventual decommissioning, and so on. The entire life.”

“And this should apply to all engineering in all fields, not just civil engineering. Anything, everything that’s engineered. They should be looking at the lifecycle of a product to ensure that it’s environmentally responsible.”

–

Barry Hitchcock, 90, and wife Betty, reside in the Toronto suburb of Scarborough. Hitchcock keeps abreast of engineering trends and issues through his memberships in Professional Engineers Ontario, Engineers Australia and as a Fellow of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering, subscription to U of T’s CivMin Alumni magazine, Alumni events, and the Distinguished Lecture Series talks.

Barry and Betty strongly believe in giving back to society through volunteering. Barry has done this through his professions, Kiwanis, community, sporting organizations and on the board of the Scarborough General Hospital.

By Phill Snel