New research from CivMin Professor David Meyer and his team highlights how water supply scheduling leads to inequity between rich neighbourhoods and poorer ones in two Indian megacities

In North American cities, the water supply is typically available 24 hours per day. In other parts of the world, the average can be far less — but according to Professor David Meyer (CivMin, ISTEP) even that reported average can mask a lot of complexity and inequity.

“You might hear a water authority say that on average, their customers receive between three or four hours of water supply per day,” says Meyer.

“What they don’t tell you is that the average is derived from thousands of individual supply schedules that vary wildly from one neighbourhood to another. Some might have water nearly all the time, while others might get it only once per week.

“What time you get water, how much you get, and how long you must prepare to go without impacts your quality of life. There is a huge need to understand that complexity and the inequity it leads to.”

Meyer estimates that more than a billion people around the world get their water from intermittent systems, in which the supply is regularly turned on and off throughout the day or week. For the past several years, he and his team have been studying various aspects of these systems.

Their latest research paper, published in Science of the Total Environment, represents the first in-depth study into the complexity and inequity within the water supply systems of two Indian megacities: Delhi, with a population of more than 32 million, and Bengaluru, which has more than 13 million people.

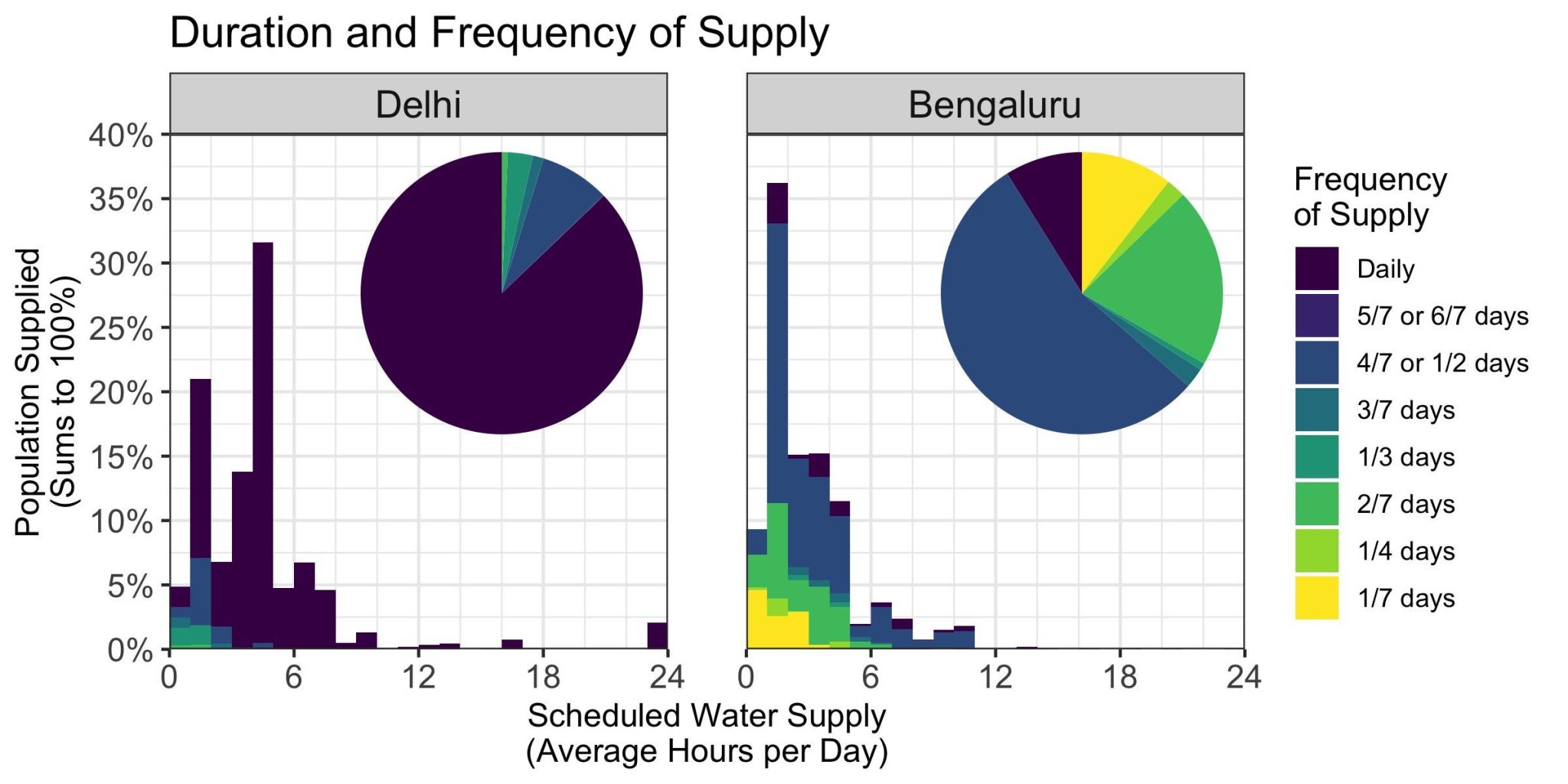

Between them, Meyer and his team found 3,278 different water supply schedules, ranging from nearly continuous to as little as 30 minutes per week. While the pattern of supply was extremely complex and differed significantly between the two cities, in general, affluent neighbourhoods tended to have better water schedules than poorer ones.

The research was sparked in part by an experience Meyer had during his PhD thesis.

“Basically, I wanted to find a reference for the average number of hours per day that water is supplied to customers in Delhi, and I couldn’t find one online,” he says.

“What I did find was 42 different posted supply schedules, none of which were in a format where the data could easily be parsed by a computer. I ended up spending a day and a half typing them into a spreadsheet so I could work out an average.”

While water authorities in Delhi and Bengaluru say they are working toward a 24/7 water supply, they post their current intermittent neighbourhood water supply schedules online as an interim measure. This practice makes good sense, as Meyer explains.

“If you live in an intermittent water supply, it’s transformative to know when the water is going to turn on,” he says.

“Now you can leave your house, or send your kids to school, or go to work without worrying that you’re going to miss water. What was surprising to me was that even within the posted schedules, there is a huge amount of variability and inequity.”

Meyer and his graduate students scoured the websites for the cities of Delhi and Bengaluru, extracting numbers to expand and complete the dataset he began during his thesis. They then developed tools to visualize and analyze the patterns they found.

In Delhi for example, about 2% of households get a water supply that is close to 24/7, but on the other end of the scale, there’s another 2% that only gets 30 minutes per week of supplied water. In total, nearly 5% of households get less than an hour of water per day, with many of these getting water only once every few days.

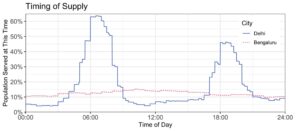

Timing also matters. In Delhi, more than 60% of the city gets water in the early morning hours, between 6 and 8 a.m. Another peak occurs between 6 and 8 p.m., reaching nearly 50% of the city. But in off-peak hours — most of the day and night — the water supply is off for more than 90% of the city.

Bengaluru doesn’t show this same temporal pattern. In that city, many neighbourhoods must wait until inconvenient times – for example, 2 a.m. – before they can get water. For most households it is only supplied on alternate days, or even less frequently.

“Frequency and duration of supply are equity issues,” says Meyer.

“If you only get water in the morning and at night, you need to invest in enough storage to last the other 10 hours. But if you only get water every other day, or every third or fourth day, you need even more storage. That costs money, takes up room in your house, gives more time for the microbes to grow in your storage tank and generally decreases your quality of life.”

The team measured inequity by looking at three factors: how many piped connections a given neighbourhood had, how long the supply lasted when it was on and how long residents had to go between scheduled supply periods.

“In both cities, rich neighbourhoods have more piped connections to homes,” says Meyer. “In Bengaluru, we also found that the rich neighbourhoods had better supply schedules, meaning that they were scheduled to receive water more frequently and for longer. This forces poorer households to invest in more water storage than rich ones.”

Meyer says that his hope for the study is that it will focus attention on the inequity that can be obscured by city-wide averages.

“Having such an enormous number of different supply schedules is already a problem, because it makes the system much more complex than it needs to be,” says Meyer.

“But given that this is the system we have, my hope is that we can unlock the learning potential from the supply schedules. If people can clearly see how unfair the current system is, I hope it will drive them to demand better regulation and more accountability for water utilities to deliver higher quality service.”

By Tyler Irving

This story originally published by Engineering News