With COVID-19 making it vital for people to keep their distance from one another, the city of Toronto undertook the largest one-year expansion of its cycling network in 2020, adding about 25 kilometres of temporary bikeways.

Yet, the benefits of helping people get around on two wheels go far beyond facilitating physical distancing, according to a recent study by three University of Toronto researchers that was published in the journal Transport Findings.

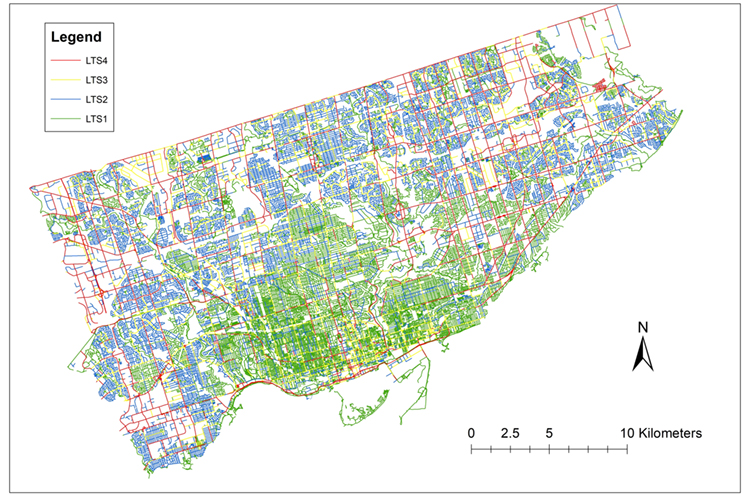

PhD candidate Bo Lin (MIE) with Professors Shoshanna Saxe (CivMin), and Timothy Chan (MIE), all of the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, used census, city and survey data to map Toronto’s entire cycling network – including the new routes – and found that additional bike infrastructure increased low-stress road access to jobs and food stores by between 10 and 20 per cent, while boosting access to parks by an average of 6.3 per cent.

“What surprised me the most was how big an impact we found from what was just built last summer,” says Saxe, an assistant professor in the department of civil and mineral engineering.

“We found sometimes increases in access to 100,000 jobs or a 20 per cent increase. That’s massive.”

The impact of bikeways added during COVID-19 were greatest in areas of the city where the new lanes were grafted onto an existing cycling network near a large concentration of stores and jobs, such as the downtown core. Although there were new routes installed to the north and east of the city, “these areas remain early on the S-Curve of accessibility given the limited links with pre-existing cycling infrastructure,” the study says.

In these areas, the new infrastructure can be the beginning of a future network as each new lane multiplies the impact of ones already built, Saxe says.

As for the study’s findings about increasing access to jobs, Saxe says they are not only a measure of access to employment but also a proxy for places you would want to travel to: restaurants, movie theatres, music venues and so on.

The researchers used information from Open Data Toronto and the Transportation Tomorrow 2016 survey, among other sources. Where there were discrepancies, Lin, a PhD student and the study’s lead author, gathered the data himself by navigating the city’s streets (as a bonus, it helped him get to know Toronto after moving here from Waterloo, Ont.).

“There were some days I did nothing but go around the city using Google Maps,” he says.

For Lin, the research has opened up new avenues of investigation into cycling networks, including how bottlenecks can have a ripple effect through the system.

The study, like some of Saxe’s past work on cycling routes, makes a distinction between low- and high-stress bikeways to get a more accurate reading of how they affect access to opportunities. At the lowest end of the scale are roads where a child could cycle safely; on the other end are busy thoroughfares for “strong and fearless cyclists” – Avenue Road north of Bloor Street, for example.

“It’s legal to cycle on most roads, but too many roads feel very uncomfortable to bike on,” Saxe says.

For Saxe, the impact of the new cycling routes shows how a little bike infrastructure can go a long way.

“Think about how long it would have taken us to build 20 kilometres of a metro project – and we need to do these big, long projects – but we also have to do short-term, fast, effective things.”

Chan, a professor of industrial engineering in the department of mechanical and industrial engineering, says the tools they used to measure the impact of the new bikeways in Toronto will be useful in evaluating future expansions of the network, as well as those found in other cities.

“You hear lots of debates about bike lanes that are based on anecdotal evidence,” he says. “But here we have a quantitative framework that we can use to rigorously evaluate and compare different cycling infrastructure projects.

“What gets me excited is that, using these tools, we can generate insights that can influence decision-making.”

The U of T team’s research, which was supported by funding from the City of Toronto, may come in handy sooner rather than later. Toronto’s city council is slated to review the COVID-19 cycling infrastructure this year.

ByGeoffrey Vendeville

This story originally published by U of T News